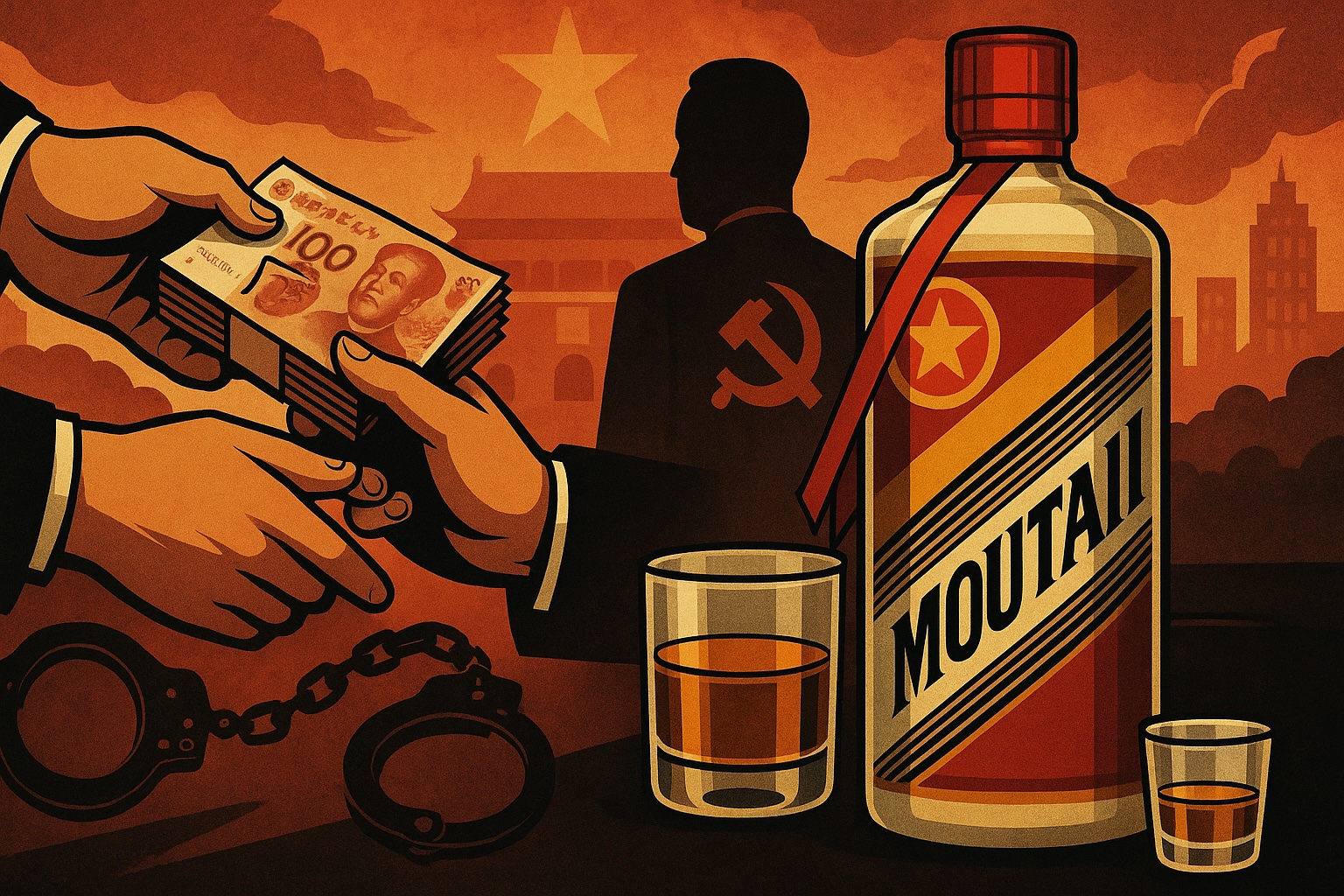

Moutai Scandal Exposes China's Elite: Corruption & Power in Every Sip

The Moutai scandal is not just another tale of elite excess—it is a revealing lens into how corruption, privilege, and political immunity operate within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Sparked by a disturbing incident in Henan Province, where a local Party official died after consuming excessive amounts of premium liquor during a political meeting, the event quickly grew into a public embarrassment for the CCP. The central leadership responded with predictable urgency, announcing a crackdown on “alcohol culture” among officials. But beneath the rhetoric lies something far more troubling: a system where luxury, influence, and corruption flow together, often bottled and branded.

At the centre of this controversy is Moutai, the iconic Chinese liquor once revered as a national symbol and diplomatic token. Today, it has morphed into a tool of political currency—offered in smoky banquet halls, exchanged in backroom dealings, and paraded as a badge of rank within the Party’s hierarchy. Investigations unearthed a flourishing underground trade in counterfeit "special supply" Moutai, falsely labelled as premium batches reserved for top-tier leadership, military units, and state ministries. These bottles, adorned with forged “internal use” labels, serve less as beverages and more as symbols of power. In reality, many are filled with industrial-grade alcohol and dressed up in opulent packaging—costing just a fraction to produce but sold at inflated rates for gifting and gain.

This counterfeit operation is not just an economic crime; it is a byproduct of the CCP’s entrenched privilege economy. Former insiders and legal experts describe a system where genuine high-grade Moutai is rarely seen outside of official circles, its circulation strictly controlled. Yet the proliferation of fakes has found favour because they feed into a ritual of status signalling and mutual back-scratching that defines intra-party relations. The deeper concern isn’t just the authenticity of the liquor but the authenticity of a governance system where luxury goods replace meritocracy.

Corruption linked to Moutai is not an isolated issue. Between 2019 and 2025, at least three senior executives from the state-owned Kweichow Moutai Group were prosecuted for corruption. They were accused of colluding with regional officials to monopolize Moutai’s distribution channels, generating illicit profits exceeding 40 million Yuan. Their arrests followed similar probes that often surface only after power struggles or factional shifts within the Party. Behind these moves lies a strategic calculus: purging enemies while rebranding efforts as “anti-corruption.” In reality, critics argue, many such campaigns are less about justice and more about reasserting centralized control.

The June 2024 nationwide crackdown where authorities seized over 318,000 fake bottles and dismantled nearly 50 criminal networks may seem like a decisive response. Over 400 people were arrested and 890 million Yuan in transactions traced. Yet the sheer scale of this underground trade exposes the broader failure of internal oversight. The challenge isn’t merely stopping counterfeits, but addressing why these commodities hold such sway in the first place: because they offer access, favour, and immunity in a bureaucratic culture steeped in opacity and informal privilege.

Wang Yuchuan, a former senior figure at the CCP’s internal anti-corruption body, offers a sobering perspective. He argues that China’s "special supply" system is not a fringe issue, it is central to how power is distributed and maintained. Every major ministry, military command, and provincial bureau allegedly maintains caches of exclusive goods ranging from high-grade liquor to imported delicacies reserved for internal use. These items grease the machinery of influence and obedience, reinforcing loyalty to the system rather than adherence to law or accountability. Wang himself recalls receiving such items routinely during his tenure, underscoring how normalized this ecosystem has become.

Crucially, the opacity of China’s media landscape makes independent scrutiny nearly impossible. Domestic press outlets are tightly controlled, and critical voices are often silenced or side-lined. That’s why scandals like these, when exposed, offer rare glimpses into how the CCP operates behind its façade of discipline and unity. Moutai, once a harmless cultural token, has become both a symbol and a symptom: of rot within the system, of governance that rewards loyalty over law, and of a political elite that drinks deeply from the cup of privilege while the nation pays the tab.

At its heart, the Moutai scandal underscores a darker reality. The real issue is not just counterfeit liquor; it is a counterfeit governance culture. In a system where luxury items dictate influence, and where the rules apply unevenly depending on status, corruption is not a flaw. It’s a feature. Bottles may be seized, and executives jailed, but until the core incentives of political survival are rewritten, the next scandal is only ever a banquet away. Every sip of elite privilege leaves the public with a bitter aftertaste, one that no anti-corruption slogan can truly wash away.

![From Kathmandu to the World: How Excel Students Are Winning Big [Admission Open]](https://www.nepalaaja.com/img/70194/medium/excel-college-info-eng-nep-2342.jpg)