China’s Coercive Trade Tactics and The Global Pushback

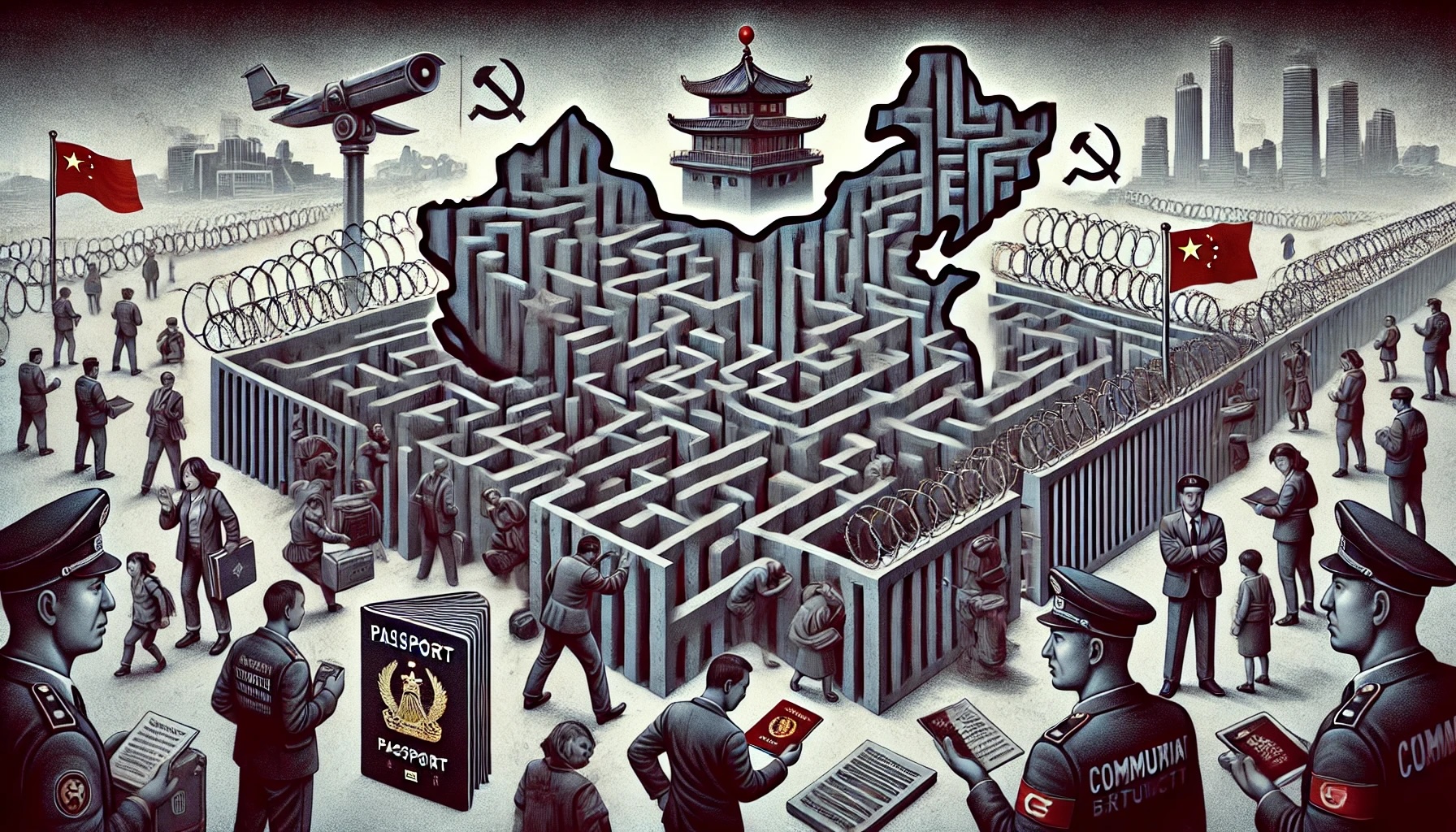

By warning other countries against sealing trade pacts with Washington and yet refusing to curb its deep‐rooted economic imbalances, Beijing is using coercive diplomacy in a way that endangers the stability of the world economy. On April 21, 2025, China’s Ministry of Commerce publicly declared it would “firmly oppose any party striking a deal at the cost of China’s benefits,” and threatened “reciprocal counteractions” against those who join hands with the U.S. Issued mere days before Indian negotiators touched down in Washington, this ultimatum underscores China’s urgency in trying to pull countries back into its sphere of influence. The very next day, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt pushed back, noting that the flood of nations seeking U.S. trade ties is itself proof of America’s economic draw. This back‐and‐forth lays bare China’s tactic of bullying to obscure its own weakening standing as the global community grows weary of its mercantilist maneuvers.

Beijing’s hard‐line rhetoric is part of a broader effort to weaponize commerce. In its April 21 statement, the Ministry accused governments negotiating with the U.S. of “hunting tiger skin,” a metaphor warning of short‐lived gains. Such language recalls past CCP appeals aimed at discouraging partnerships with Western democracies. Indeed, China’s imposition of 125 percent duties on American products—alongside threats to choke rare‐earth exports—seeks to stymie U.S. manufacturing. Yet these measures have often had the opposite effect: in 2024–2025, U.S. trade volumes with Vietnam, Malaysia, and India climbed by 18 percent as companies diversified their supply chains away from China.

But China’s bullying tactics clash with its own WTO obligations. As a member, it is bound by the non‐discrimination principle under GATT Article I, which demands equal treatment of all trading partners. By insisting that nations prioritize Chinese interests over new U.S. agreements, Beijing is flouting the very rules it helped establish. In leveraging its enormous market to intimidate smaller economies, China is chipping away at the multilateral framework it professes to support.

At the heart of this aggression lies an economy groaning under its own state‐driven policies. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and other White House advisers have warned of a looming “China Shock 2.0,” driven by massive subsidies for electric vehicles, solar panels, steel, and other key industries. Chinese‐backed factories now account for roughly 60 percent of global EV output and 80 percent of solar modules—volumes that far outstrip domestic consumption. With industrial output up 7 percent year‐over‐year in April 2025 while retail sales grew only 2 percent, China is offloading underpriced goods onto world markets, warping the level playing field.

History offers a cautionary tale in the original “China Shock,” which erased some 3.4 million U.S. manufacturing jobs in the early 2000s. Yet, as National Economic Council Director Lael Brainard has observed, “China has grown too large to flout its own rules.” The Biden administration’s decision to impose a 100 percent levy on Chinese EVs—and the Trump administration’s even higher 145 percent blanket tariffs—reflects a bid to counteract China’s trade distortions. Beijing’s retaliatory measures, such as delaying Boeing deliveries and restricting rare‐earth shipments, show it is willing to disrupt global supply chains for strategic advantage.

Meanwhile, China portrays U.S. tariffs as “unfair” while maintaining its own protectionist barriers. It still levies 125 percent duties on American agricultural exports and uses its Great Firewall to limit foreign tech access. China’s fiscal firepower is also far greater: its $586 billion stimulus in 2008 and the current $1.2 trillion subsidy program dwarf Washington’s efforts to onshore critical industries.

China’s latest WTO challenge to U.S. tariffs exemplifies this double standard. By contesting America’s right to defend itself against dumping, Beijing aims to legitimize its state-capitalist approach while denying others the same countermeasures. As Karoline Leavitt put it, “China is no different from any other country—only much larger.” The U.S. position, supported by both parties on Capitol Hill and a growing list of allies, is that tariffs will stay in place until China ends forced technology transfers and intellectual property theft.

Faced with Beijing’s zero-sum demands, more countries are charting an independent course. India pressed ahead with talks in Washington despite Chinese pressure. The European Union has slapped new anti-subsidy duties on Chinese EVs, and Japan is heavily investing in U.S. semiconductor fabrication. Even developing economies are recalibrating: Vietnam’s U.S. trade rose 24 percent in 2024, and Malaysia has cut its reliance on Belt and Road financing by 40 percent.

This shift reflects China’s failure to offer genuine reciprocal benefits. Its “dual circulation” strategy, which aims to boost domestic consumption, has faltered—household spending still accounts for only 38 percent of GDP, compared with 68 percent in the U.S. Countries recognize that deeper ties with China risk locking them into a market that’s losing momentum, whereas U.S. partnerships promise access to innovation and consumer-led growth.

China’s menacing posture toward U.S. trade diplomacy marks a pivotal moment for the rules-based international order. By conflating its own ambitions with the common good, Beijing may hasten its own marginalization. The United States and its partners should respond in unison—strengthening tariff enforcement, broadening the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, and exposing China’s subsidy schemes at the WTO.

As Karoline Leavitt said, “The ball is in China’s court” to move away from coercion and engage constructively. Until that happens, democracies worldwide must bolster their economic defenses to ensure the coming decade is defined not by another “China Shock,” but by durable, inclusive prosperity.

![From Kathmandu to the World: How Excel Students Are Winning Big [Admission Open]](https://www.nepalaaja.com/img/70194/medium/excel-college-info-eng-nep-2342.jpg)